|

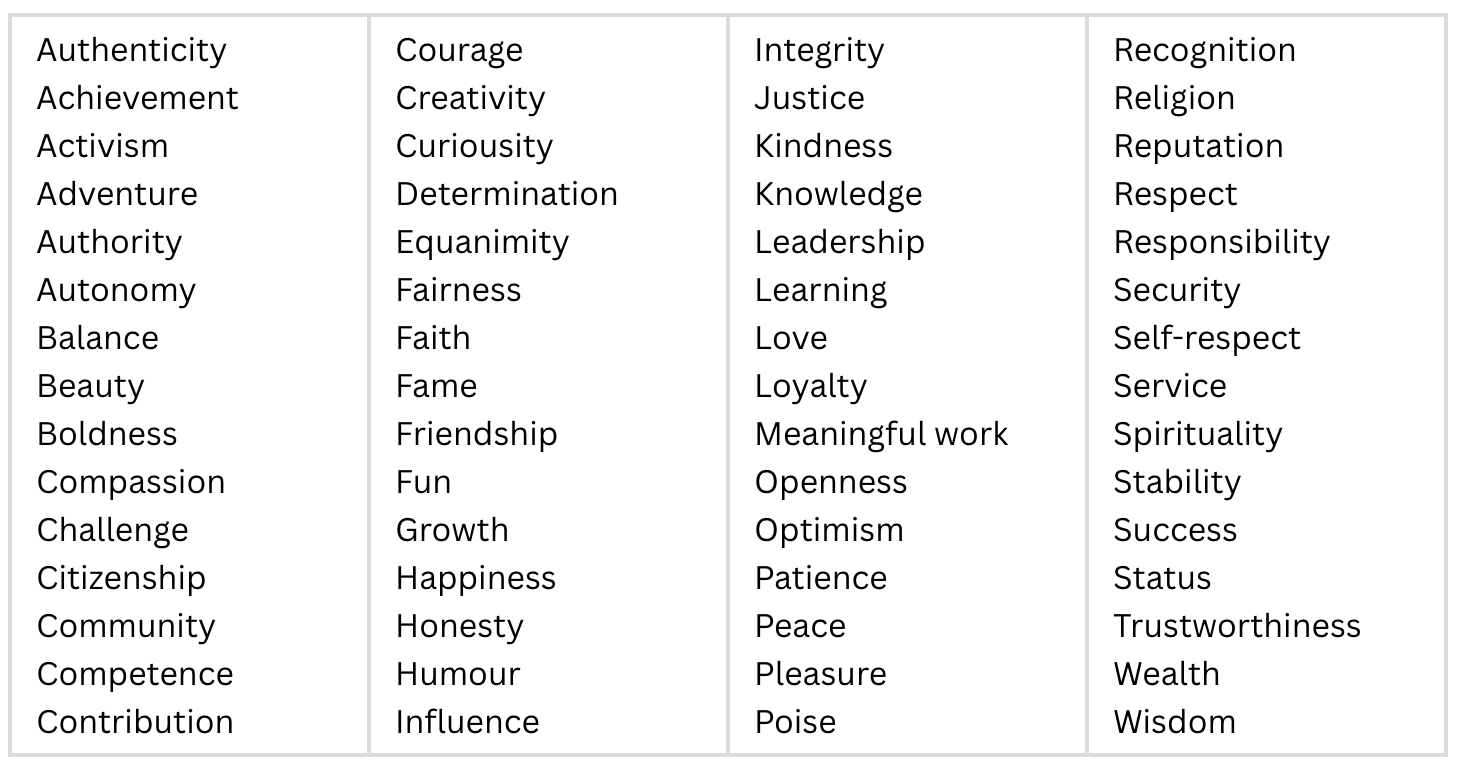

In the midst of our fast-paced world, we often find ourselves caught up in a whirlwind of distractions, daily hurdles, and those pesky little stressors that, when combined, can leave us feeling somewhat disconnected from what truly matters in our lives. It's almost as if we're running on autopilot, letting life happen to us rather than seizing the reins as the authentic creators and directors of our own destinies. When the scales of life tip towards imbalance, when stress creeps in, or when a general sense of dissatisfaction lingers, it's not uncommon to feel adrift from our core values. Our values are the quiet, underlying principles that define what matters to us. They're kind of like the invisible threads that weave the fabric of our existence. Values provide us with direction, acting as the framework upon which we build our lives. In moments when we stand at crossroads, uncertain of which path to choose, it's our values unfurl before us like a trusted roadmap, guiding us toward authenticity and purpose. So, as we welcome 2024, I extend a heartfelt challenge to you: let's endeavour to live each day steered by an awareness of what holds significance to us—your core values. Here's How:1. Identify your Authentic Values: Explore the following list of values, and choose the top 6 that represent your authentic values  2. Embody the Meaning: Dive deeper into the meaning of each value you selected: look up the definition of the word, and seek to understand its essence and significance. 3. Align your Choices and Actions: Ask yourself, what does it truly mean to embody this value? How can you infuse it into every facet of your daily existence? And, consider how you'll translate each of these values into daily action. Actions speak louder than words, after all. 4. Devise a Plan to Stay on Track: To be intentional with living your values, create a check-in routine. Whether it's once a week or once a month, this reflection is crucial. If you're concerned about forgetting, here are 3 suggestions for how to remember to check in:

A few final points to remember:

Living your values invites deeper self-awareness into all you do - you foster a greater sense of integrity with self, congruence, and fulfilment. I am so excited for the magic to unfold, as you create your daily life in ways that align with your values and aspirations. I'd love to hear what this exercise was like for you - leave a comment, or better yet, let me know what your top 6 values are!

0 Comments

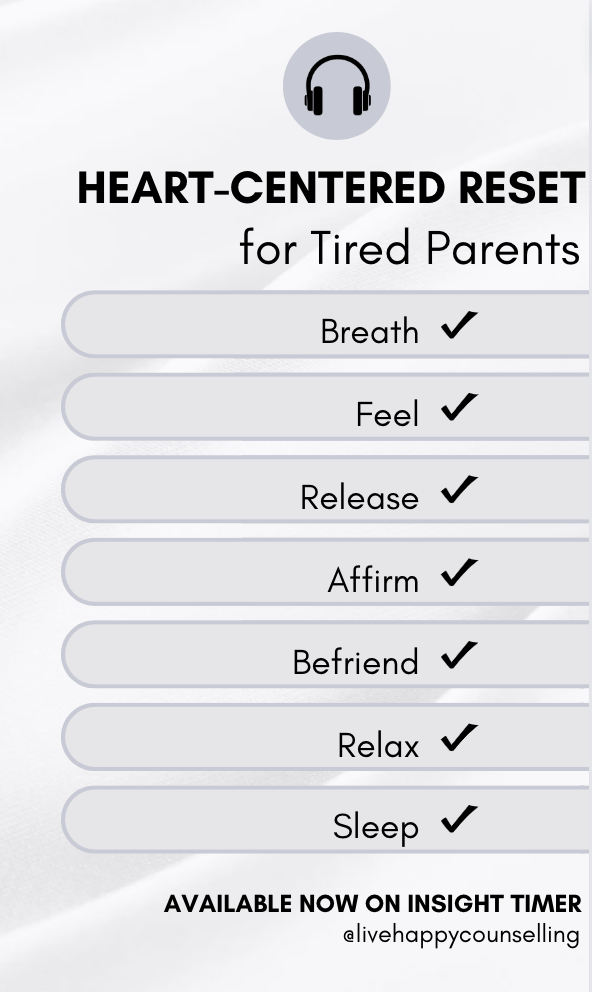

An Emotion Regulation Course Designed for Parents

Course DesignThe course blends mindfulness, emotion regulation, attachment theory, and brain-based parenting, and it's designed for all parents, irrespective of your children's age. There are 6 lessons and 1 guided sleep meditation. Each lesson is approximately 20 minutes in duration, and includes: - a brief informative lesson - an emotion regulation strategy - a guided practice (meditation) - a home practice suggestion Course Outline

Parenthood can be tough. And when things get tough, we can all use a bit of help. This course is about developing a healthy habit with emotion regulation so that you can handle the tough moments that come your way - it’s about rejuvenating you, the parent - so that you can re-discover, re-energize, and re-centre in the present moment.

When we approach the day with mindful awareness and the ability to settle strong emotion when it bubbles up, we are more present with others and experience greater ease in bravely showing up as our authentic self. If this sounds interesting to you, please give the course a go! Learn more and sign up for the course on the Insight Timer app, at A Heart-Centered Reset for Tired Parents How often does the strong pull of anxious thinking lure you into its’ loop of incessant worry, what-ifs, and not-good-enoughs? Spending time on the thoughts that worry and anxiety drive you to think about isn’t the best the way out of it. In fact, thinking the thoughts that accompany anxiety often breeds more anxiety. We need a way out of those thoughts. One that calms our body and our mind, so that we can more accurately and compassionately deal with the experience. The RAIN meditation by Tara Brach offers just that.

The RAIN meditation is an excellent way to steer out of anxious thinking cycles, deepen compassion and connection to self, and anchor back into the present moment. Take a moment and play with these 4 steps, to build self-compassion and step out of stuck thinking. This is my public service announcement about kindness during COVID. Also known as ‘don’t be a dick’. If someone forgets to sanitize their hands when entering a store or enters without donning their mask – a kind reminder is all it takes. And if they can’t don a mask due to medical reasons – please listen with understanding, not judgment or resentment. Seek first to understand.

When we react with anger, it’s like we take the behaviour of others and stab ourselves with it. Then we project our hurt onto them and view them as the villain. No one here is the villain. There is no us against them. We are all in this together. Every single one of us. So please, if you are feeling grumpy, take a moment to care for yourself. If you find you’re feeling angry or impatient when around others, try these super simple tips: Have you ever been at a loss for what to say when someone you know is having a hard time? Show you care by speaking from your heart. Try one of these statements:

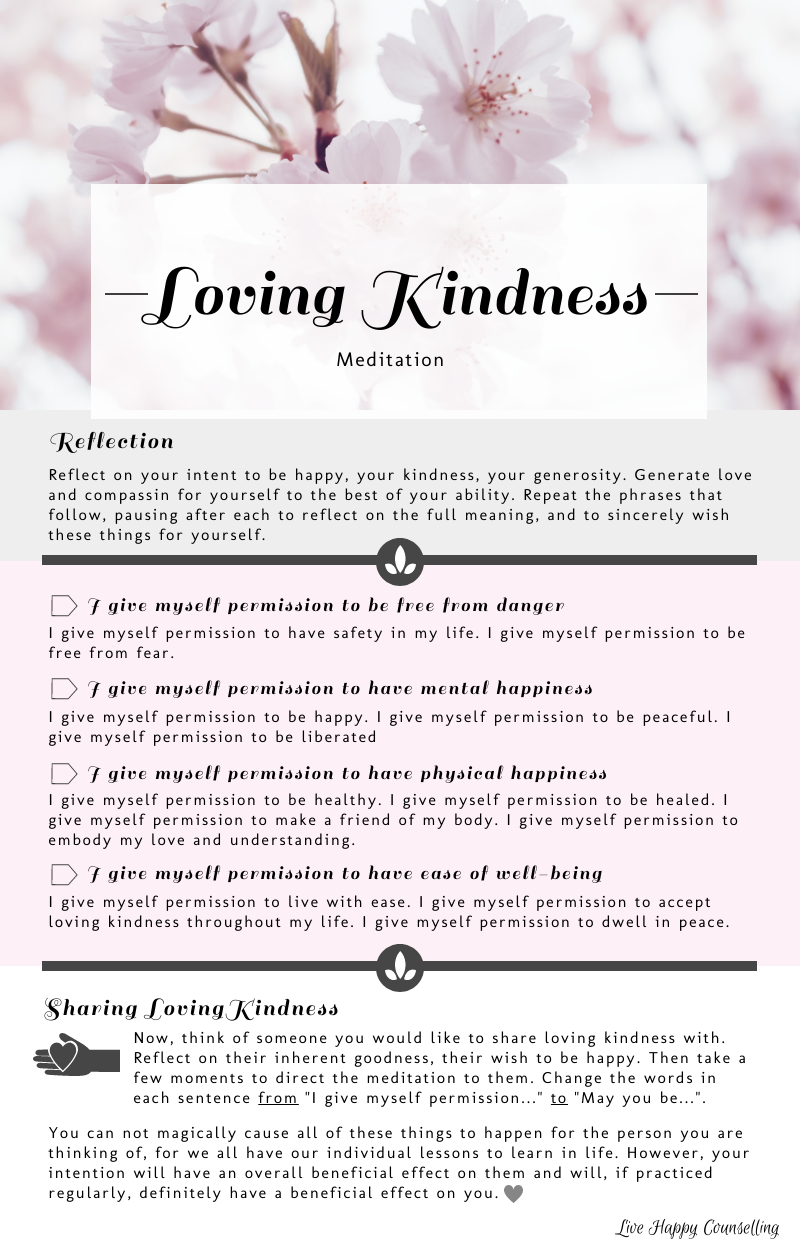

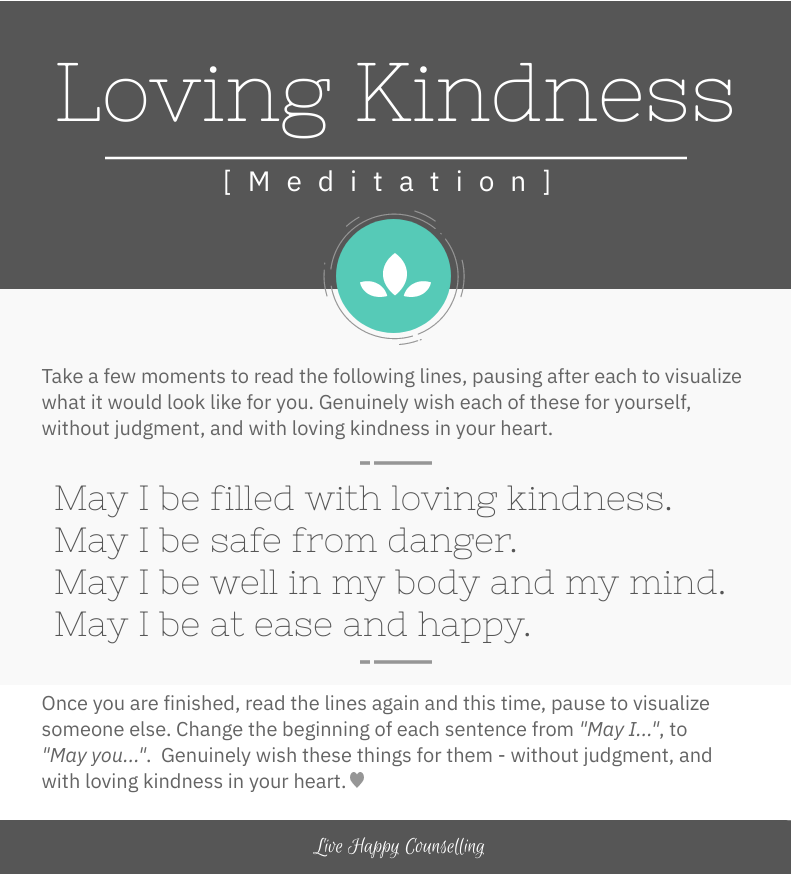

Show up, be available, talk about the tough stuff. The truth is, at any time in our lives, any one of us may struggle emotionally. What would you need if it were you? Thinking about what you might need to hear can help you if you aren’t sure what to say. Remember, not everyone who is struggling will show that they are struggling. As a general rule, treat people with kindness and seek first to understand before making judgments. Any ideas to add to the list? Please share your suggestions in the comments – helping each other will ripple out to help the people we encounter. 2022 update: Audio Track now on Insight Timer! Check out the full-length version and the children’s version I first learned the loving-kindness meditation during a training course. I had been so taken by it that I immediately began integrating it into my personal life. Over the years, I have brought it forward into my counselling practice. The loving-kindness meditation comes from the Buddhist tradition as a means to develop compassion. Its simple sentences aim to foster unconditional acceptance, love, and compassion for self as well as for others, with no expectation of anything in return. In this post, I am sharing two versions of the loving-kindness meditation. The first one is longer and may take approximately 10 minutes, and the second one is abbreviated for those days when we feel pressed for time. Here are some suggestions on when to use the loving-kindness meditation:

The loving-kindness meditation can help you cultivate compassion for self and others. Challenge yourself to use it daily for 2 weeks, and notice with curiousity the beneficial impact it can have on you and your relationships! Resources:

Physical fitness has long been a go-to stress reliever in my life. However, at times I have to admit: I wasn’t full present during workouts. My thoughts can be loud, especially the ones that centre around things I “should have” done differently, or to-do lists for the day. The more these nagging thoughts would get in, the more I would lose my mojo and want to end the workout. Then I would feel bad, and stress would actually increase during the very thing that I was doing to decrease stress. Sound familiar? When we get caught up in thoughts of the past or future, or get stuck in negative thoughts, we actually set off a stress response in our body. And, the part of our brain we rely on to keep us engaged and focused in the present moment goes off-line. Our thoughts and emotions change our awareness. If we suddenly found ourselves ruminating on negative thoughts, our outlook will shift and we will lose energy and focus for the task at hand. Mindfulness is all about being fully in the present moment, with loving kindness in our heart, and without judgement. When we take the time to cultivate mindfulness, we learn that we do not need to “get hooked” by our thoughts. We learn that we can watch the chatter of our mind, to extend compassion to ourselves as needed, and become better able to shift focus back into the present moment. Returning to the Present Moment: Daily Practices to Cultivate Mindfulness

There are books and workshops and retreats designed to help individuals cultivate mindfulness. These are all brilliant ways to start a new habit. But they can take time. Here are a few strategies you can use right now to bring mindfulness into each day and ultimately, into each of your workouts. Make a plan: When we are learning something new, we are far more likely to successfully learn it when we have a plan, and when we create time for practice. Create your plan: one way to cultivate mindfulness is to take a moment each day to focus on your breath, to get fully into the present moment. If you need help getting into the moment, or need guidance on slowing and deepening the breath, try an app. Some good ones are Insight Timer, the Calm App, and Mindfulness Daily. If you do not need guidance but find that you don’t remember to check in, set some alarms on your phone to go off during the day. Give these alarms descriptive names such as: Now is a great time for 1 minute of deep breathing, and Daily Check-in: how are you feeling in your mind and body? Make time to practice: Life will always be busy. The world of today has conditioned us to hurry, to multi-task. The cost is this lifestyle is that we constantly feel rushed. If we do not learn to pause, we risk living every day with a sense of urgency, an urgency which on its upside enables us to be productive but on its downside breads anxiety and seeds a sense of inadequacy. Slow down, allow yourself to pause: we can all afford a few minutes each day to connect with mindfulness. Take the moment to focus on your breath and to return to the present moment. Set your intention before you workout: before you being your workout, take a moment to breath deeply and set your intention. Setting an intention will give your workout direction. Think of it as a road map: we might not need it on our road trip, but if we get lost it sure is necessary to get us back on track. Today during my spin class my intention was “I will just be present and do my best”. Each time I noticed my mind drifting, I was able to return to my intention with loving kindness. What does that look like? It is noticing my thoughts had drifted by saying “there I go again…” and then repeating my intention. Use a mantra: Mantras are statements we say repeatedly and which have significant power in impacting our attention, outlook, and mood. You can use any statement that works for you to bring your attention back to the present moment. What words do you need to repeat to yourself to stay in the moment of your workout? It could be “Right Here Right Now” or “Strong and Fit”. If you listen to music while working out, use the beat of the music as your repeat the mantra to yourself. When all else fails, count: When we are counting, intrusive thoughts are less able to enter our awareness. That is why knitting can be so grounding for people: they have to count stitches. There are many ways to use counting during a workout. You can count your reps; if you are walking or running you can simply repeat 1-2-1-2-1-2 as you shift your weight from foot to foot. Our thoughts will always be there. Mindfulness just lets us choose when and how we will attend to them. Using a few simple mindfulness strategies when exercising can enable you to derive more enjoyment from it while also cultivating compassion and self-acceptance. You might even experience an increased sense of accomplishment because you were fully present for something you set out to do. Taming your Monkey Learning to be focused in the present moment can be challenging. I don’t believe this is just the case for those who have experienced trauma, or for those with anxiety. I believe it is a symptom of fast-paced society, where we are driven to do more and where flashy technology and advertising vies for our attention. Often when we try to concentrate, our minds have a tendency to wander. It just takes some focused attention (and patience with yourself) to learn to be present and in the moment. A distracted mind has even been referred to as ‘monkey mind’. I imagine this as having a monkey contained in a room – he’d be jumping from one piece of furniture to another, climbing the ways and hanging on the curtain rod or blinds - and all the while chattering incessantly. It is in this way that our minds tend to do the same: engaging in an endless flow of dialogue, jumping from topic to topic. If you are trying to focus your attention in the present moment, please do not be discouraged if your mind wanders! It is natural. Everyone has ‘monkey mind’ from time to time! Reassure yourself that it takes practice to become mindful, to be in the moment and aware of your thoughts without judgment. If, while using a grounding or containment strategy, you notice your mind wanders, please be patient with yourself. It’s hard to learn a new skill; do not put yourself down or call yourself names. Most likely there have been enough people across your lifespan who have done that. Simply notice that it happened, be kind to yourself, and return to where you left off. Article originally posted 2014/02/20 posted by Susan Guttridge (susanguttridge.wordpress.com) Resources: Tolle, E. (2003). Stillness Speaks. Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Guided Mindfulness Meditation, Series 1. |

AuthorSusan Guttridge is a trauma-informed Master level Counsellor with the clinical designation of Canadian Certified Counsellor (CCPA). She has 20+ years experience providing individual and group therapy. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed