|

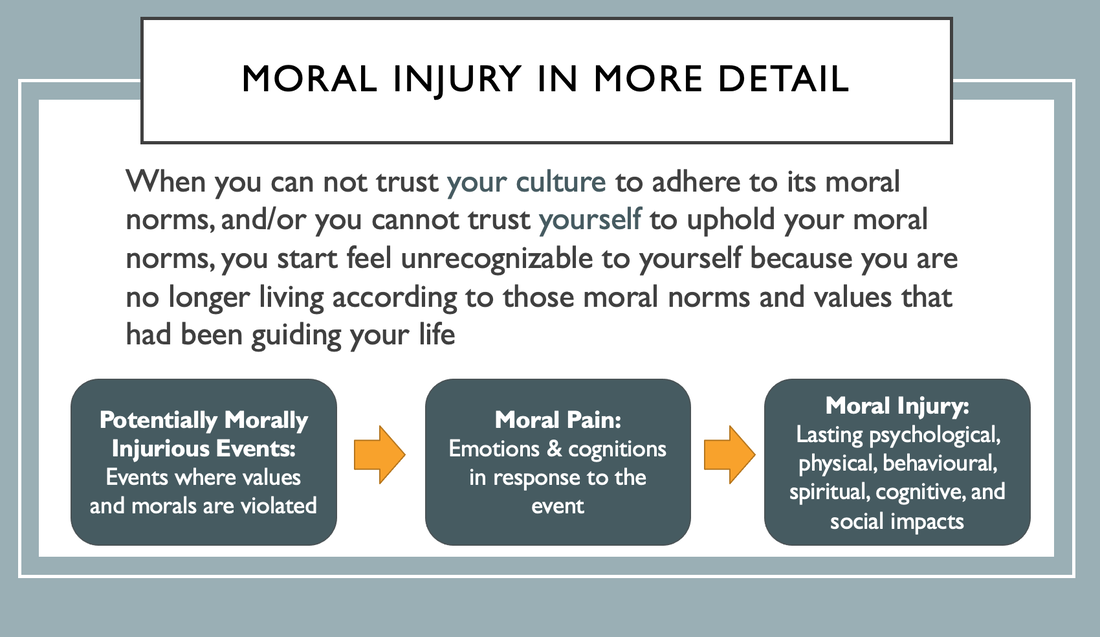

Moral injury is rooted in a violation of personal values. It’s an important concept but it is one that many people haven’t heard of. It refers to the extremely distressing psychological, behavioural, cognitive, and spiritual aftermath of exposure to events that violate our sense of ‘what’s right’. Regardless of if these morally injurious events were through commission, omission, or betrayal, the lingering consequences on a person’s sense of self are tremendous. Main Points

Introducing the Concept: Moral InjuryThe term moral injury was first coined by psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Shay (1991), who saw the symptom first among the military veterans he was working with and who described it as the physical, social, and psychological results of a betrayal of what’s right. Moral injury is a loss-injury, a fracturing of one’s sense of self, and a disruption in trust (of self and others) that occurs within one’s moral structure. Any events, actions, or inaction transgressing one’s moral and ethical beliefs, expectations, and standards set the stage for moral injury. A betrayal on a personal or organizational level can act as a precipitant. The Link Between Moral Injury and Post-Traumatic Stress (PTSD Moral injury is separate from PTSD, and there is presently no diagnostic category for moral injury. A moral injury doesn’t mean that a person fits the criteria for post-traumatic stress, a PTSD can be present without a moral injury. There are similarities in symptoms between moral injury and PTSD. When a moral injury is present with PTSD, the diagnosis of PTSD does not sufficiently capture moral injury or the shame, guilt, and self-handicapping/sabotaging behaviours that often accompany a moral injury. In cases where a person does experience both PTSD and moral injury, the moral injury layer often goes unidentified. Opening up dialogue about moral injury and recognizing the signs can help improve treatment outcomes. Moral Injury and Public Service PersonnelJournalist David Wood writes that “moral injury is the signature wound of today’s veterans”. So what is it about this population and all first responder/Public Service Personnel that puts them at greater risk of experiencing a morally injurious event? During training, military personnel and first responders learn to function under the philosophy that the mission is more important than their personal comfort. They learn to compartmentalize for the sake of adapting and overcoming the challenges of performing their duty effectively. In other words, they learn to ignore their inner experiences. While this enables them to efficiently carry out the duties of their job, there is a splitting off, or a separation of their human experience as a means of avoiding the mental discomfort and anxiety caused by traumatic witness, conflicting values, cognitions, emotions, and beliefs within themselves. There is utility to this: allowing one’s inner experience opens the flood gate for doubt, anxiety, or fear to bubble up to the surface which could lead to a sense of vulnerability – and in their job they must elude a sense of invincibility and power. Everything these individuals do in training is about shutting out the inner emotional experience in order for the mission to remain the primary focus. Essentially, these individuals learn to override their natural stress response in order to complete work-related tasks, which is referred to as function over feeling. For many military and first responders, their profession becomes the prominent feature of their identity, with the suppression of the emotional side becoming entrenched. This, combined with the constant exposure to potentially morally injurious events regularly as part of their job put these individuals at higher risk of developing a moral injury. Moral injury creates an important cognitive dissonance between one’s morals and actions, resulting in a wide range of symptoms Symptoms of a Moral Injury The core symptoms of a moral injury include:

Moral Injury and Help-Seeking Behaviour Because shame sits front and centre in a moral injury, the injury itself may act as a barrier to accessing help and recovery. These individuals often feel ashamed, guilty or angry which can make them very reluctant to talk about their difficulties. And because it remains unspoken, they are unable to process and make sense of the internal moral conflict. The Experience of Shame:Shame is a fear-based internal feeling state. It brings with it a painful, intense and fundamental sense of inadequacy, worthlessness, and lack of belonging. More than a sense of “I made a mistake, I did something bad”, which is guilt, shame screams throughout every fibre of one’s being “I am a mistake, I am bad”. Shame can create extreme self-consciousness, a feeling as though not only are they less than, but that everyone can see it. Shame can erode one’s sense of self and become the lens through which they view themselves. And because it feels so painful, we tend to fight furiously to suppress it and stay quiet about our experience of shame. And with anything uncomfortable, our unconscious defense mechanisms can be activated. As you can imagine, for those living with a moral injury, the majority of their time and energy is consumed with symptom management and not living. The defense mechanisms we employ to escape from shame can come to take on a life of their own – our very own internal puppet master constantly directing our behaviour and reactions. Brené Brown describes these as ‘shame shields’. A person may have a pattern of moving away (withdrawing, secrecy), moving towards (seeking to always please and appease), or moving against (confronting shame with shame, attempting to have power over others, using aggression). Developing Shame Resiliency There is another option though: in the face of shame it is possible to courageously voice it. Shame resilience refers the ability to recognize shame when it flares up and move through it in a constructive way, one that allows a person to align with their allies through communicating the experience, thus maintain their authenticity and reducing the pain of shame. A central part of developing shame resilience involves empathy. Empathy refers to the ability to view the world the way another person views it, without judgment – recognizing their emotional experience through their lens. Empathy communicates to another person that they are understood, and that they are not alone. Whereas shame convinces us we are alone, empathy communicates the opposite. In this way, empathy becomes an antidote to shame. In addition to learning to connect with empathy and seeking a listener who is empathetic, there are additional things we can do to develop resiliency to shame. Here are 4 additional ideas:

Healing Moral Injury If the course of their training teaches Public Service Personnel to separate the two sides of themselves (the person who is on the job, and the person in all other domains of their life), then healing must involve working collaboratively with these two parts in order to resolve the moral injury, to resolve the inner conflict. It involves reconciling both parts of self: the stoic part and the empathetic part. And this starts with sharing it: communicating the trauma and the moral injury that occurred with someone who gets it. The listener has to have an understanding of moral injury because the shame and anger can run so deep alongside the injury.

A counsellor trained in trauma work, including the impacts of post-traumatic stress and moral injury, can work with an individual to recognize and heal:

To foster an environment that supports individuals in healing a moral injury, we must start up opening up the dialogue around moral injury and shame. Learn more what a moral injury is, and start talking about it. Notice when shame flares up in daily life, and talk about it with someone who can empathetically hold your story. ** This article is based on the presentation I made to the participants attending the Dr. G. Davidson Operational Stress Recovery Program in Vernon, BC. Please click the link to learn more about operational stress recovery and the programs offered at their clinic. Check out the links below to learn more about moral injury.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSusan Guttridge is a trauma-informed Master level Counsellor with the clinical designation of Canadian Certified Counsellor (CCPA). She has 20+ years experience providing individual and group therapy. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed